To collect good data, you need to design good forms. A well-designed form helps well-meaning people to provide good data and makes it difficult for bad actors to provide bad data.

We work with Open Ownership to support governments in collecting data about who ultimately owns and controls companies. Beneficial Ownership refers to the natural person(s) who ultimately has the right to some share of a company or legal entity’s income or assets (ownership) or the right to direct or influence the entity’s activities (control), either directly or indirectly.

We’ve been working together to understand how we can improve disclosure forms — the means by which beneficial ownership is declared — and have developed a number of different methods to support this work.

While some of the challenges we’ve faced are unique to beneficial ownership disclosure, we’ve also learnt some broader lessons about designing good forms and building resilient data infrastructure overall.

In this lightweight version of our methodology, we explain how we review and assess data collection forms with three questions, asked in order:

- Are you clear what data you’re collecting?

- Have you structured the form to make it easy to complete?

- Are you making it easy to capture the best quality data you can at field level?

1. Are you clear what data you’re collecting?

In order to create a form you need to know precisely what data you need to collect. For beneficial ownership and other legally mandated types of disclosure, this is defined in legislation and regulation.

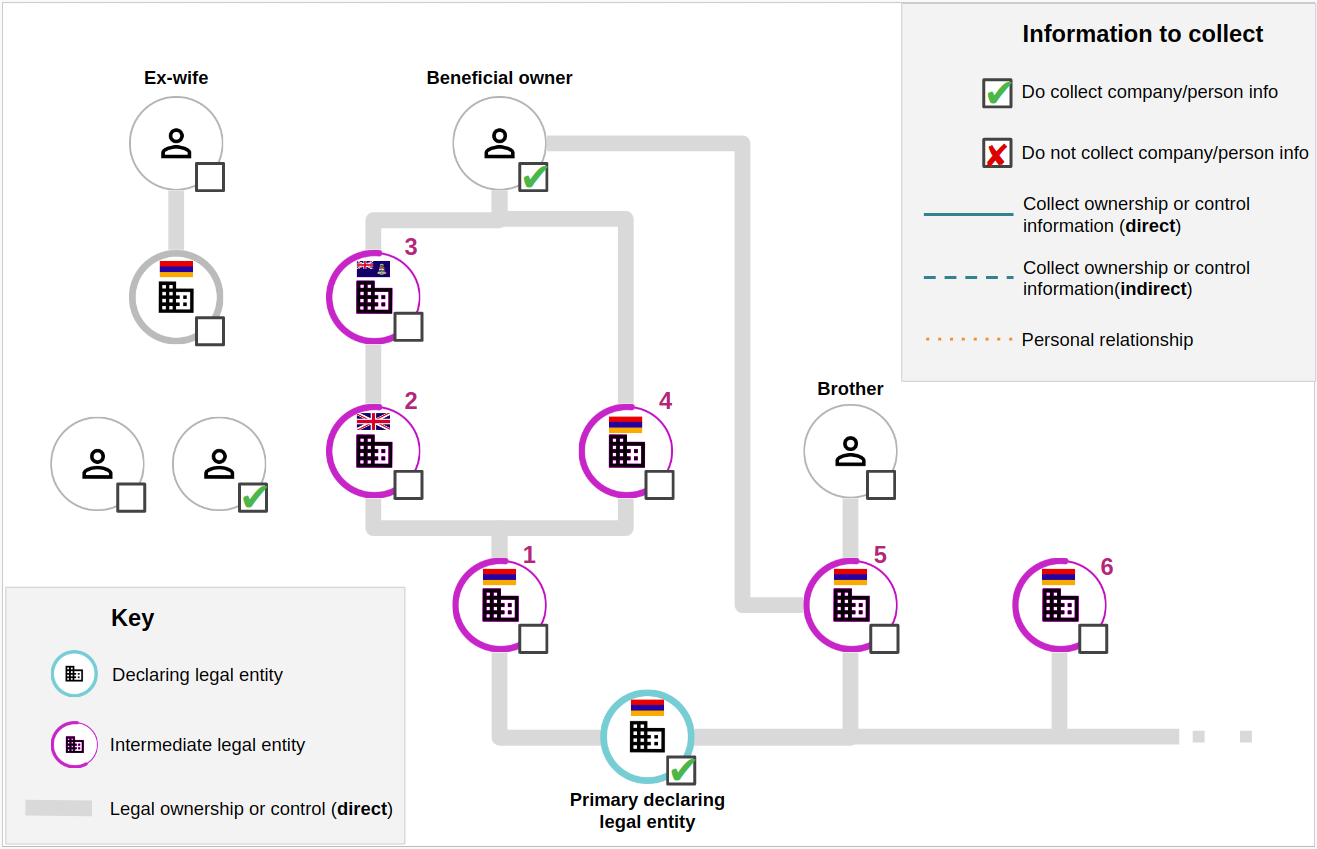

Disclosure frameworks — the legislation and regulations which mandate disclosure — are the filter between real world situations and the data that is published. When we look at the scope of disclosure, we’re looking for the definitions and thresholds that determine whether certain relationships with a company have to be disclosed.

Legislation is seldom designed with data collection in mind. Sometimes secondary legislation is passed that specifies data that should be captured by beneficial ownership systems. Sometimes it is left up to officials to resolve the ambiguities because the legislation has not been explicit.

In an ideal situation, OpenOwnership works with lawmakers and civil servants drafting the legislation before it is enacted to establish the scope of disclosure. Where our work begins later on in the implementation process, we use this exercise to explore problematic real world situations, or to test our understanding of the disclosure framework.

Reviewing the scope of disclosure allows us to:

- Clarify, or help shape, the scope of disclosure defined in law

- Test people’s understanding of what information should be disclosed

- Explore the implications of different interpretations of a particular scope of disclosure

- Expose ambiguities in the scope of disclosure defined in law

- Represent cases where forms fail to collect required or important information

- Clarify the scope of disclosure for a particular company structure of ownership and control

Have you structured the form to make it easy to understand and navigate?

Simplifying disclosure by reducing the mental overheads on people filling out the forms reduces the chances of genuine errors entering the system. In the case of beneficial ownership data — and other datasets that can be used to uncover corruption — these accidental errors can obscure cases of deliberate falsehood.

Before looking in detail at the questions a form asks, it’s important to understand and clarify the structure. There is a lot of complex data beneficial ownership forms need to collect, and sections of data may need to be completed multiple times. This makes it difficult to create a clear, well structured form. If the structure of a form is challenging to understand and navigate, then that should be dealt with as a priority before looking at the way the form asks for information.

To help us build a structure, or understand how a person navigates an existing form as they complete it, we use flowcharts. These offer a summary of how the relevant details of the people and legal entities that fall within the scope of disclosure are captured, as well as flagging gaps and inefficiencies in design.

Not all existing forms will require a flowchart to understand how a user is supposed to fill it in. If a form doesn’t need a flow chart, it might be overly simplistic and push too much responsibility onto the user or into the background, failing basic usability tests. Alternatively, it might have excellent signposting and navigation prompts and features, so its structure is self evident.

Reviewing the structure of forms allows us to:

- Clarify decision making and navigation

- Spot any logical errors in the form

- Understand and communicate how parts of the disclosure process fit together

- Check that all of the ownership and control relationships within the scope of disclosure are covered

3. Are you making it easy to capture the best quality data you can at field level?

Once we’ve defined the scope of disclosure and reviewed the structure of the form, we conduct a field-level review.

First, we check the quality of each question or field in the form. We’ll ask if the information the person is being asked to provide is clear? Is the format of the answer clear? Have all the concepts needed to understand this point already been explained? Are the fields grouped and ordered logically within the established structure of the form?

Second, we check the completeness of the data against the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) Schema. As beneficial ownership data helps trace ownership and control across multiple jurisdictions, it’s important that forms are designed for a worldwide perspective, not just a national one. Some common issues we see include asking for company identifiers without including the registration agencies, or making assumptions about name conventions.

Conducting field level and instruction analysis allows us to:

- Understand what users are being asked to understand and do

- Provide a basis for working with civil society if there are ambiguities and loopholes in the disclosure framework

- Assess if it meets the BODS schema to help make beneficial ownership data useful, usable and in use.

Building feedback loops

We’ve deliberately designed this process to be useful at all stages of implementing beneficial ownership transparency.

Where registers have been created and forms have been built, we can highlight any ambiguities or loopholes in the disclosure pipeline to law makers and civil society, helping to improve the disclosure framework set out in legislation and regulation. Where new registers are being implemented, we’re able to build on their work.