Rob Redpath is the product manager for most of the co-op’s software products. He works with clients, analysts and developers to ensure that the software that’s developed is the right solution to users’ needs. He has a BSc in Internet Computing and an MA in Mission, and this parallel pursuit of technical innovation and understanding people has defined his work for nearly a decade.

So, you publish some open data?

That’s great. If you’re getting the basics right, people can get your data easily, open it with free software, know what they can and can’t do with it, understand its structure, uniquely identify things within it, and connect it to other data sets. But how do they find out what it means? Or, to put it another way — how can a person wanting to work with your data, and use it with other data, work out what it means?

At Open Data Services, we build open data standards, and we see every day just how different everyone’s idea of the same concept is. We know that data is an imperfect way of rendering the world, embedded with world views, opinions and assumptions.

An open data standard won’t give everyone the same perspective on a subject, but it will help them make their perspective explicit. For people using that data standard, it helps to ensure those assumptions are the same as other people’s (or at least as similar). Ideally, it also comes with a feedback loop that enables the standard to be iterated on and improved, as it is used in more contexts.

In short, standards give meaning to data, and help users to understand the information contained within a dataset. If we’re aiming for genuine openness — instead of merely appearing open — data standards provide a framework that helps us to be transparent about our interpretations as well as the data.

What even is an open data standard?

A data standard describes both the structure of the data, and what each item within the data means. An open data standard builds on that, by being freely available, stipulating that data using it must be available for anyone to use for a range of purposes, and often by being maintained by the community, in public. Really good open data comes with an instruction manual — what the fields mean, what the scope of the data is, how to understand what you’re seeing. With a standard, that manual’s written for you. If you’re not using a standard, you need to write that instruction manual yourself.

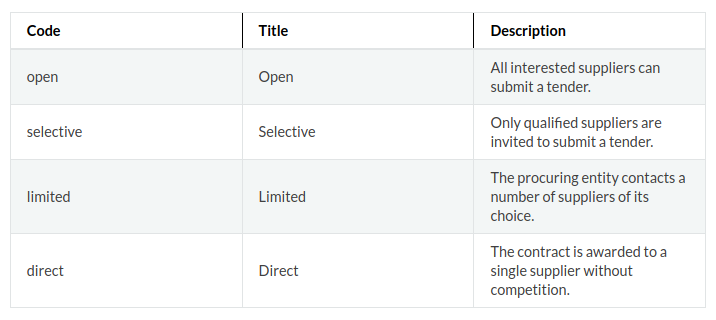

For example, the Open Contracting Data Standard defines a common data model to describe the processes that governments use to procure goods, works and services. The exact process used to buy something can vary based on what is being procured and the value of the purchase, as well as other considerations.

A key difference between contracting processes is the level of competition; some purchases are made directly from one supplier, whilst others involve inviting bids from several suppliers. Each government defines its own procurement procedures and there can be many different procedures in each jurisdiction. This makes sense; the process for procuring £100 of printer paper should be different from the process for procuring a multi-billion pound new rail line.

But, understanding which processes are competitive can involve reading the associated legislation for each procedure type. This makes it especially difficult when carrying out analysis across different jurisdictions.

To address this issue, OCDS defines a classification of procurement methods against which publishers categorise their procedure types.

This makes it much easier to assess the level of competition in different contracting processes without requiring country-specific expertise. The exact procedure type is provided in a separate field, so detail isn’t lost for those who need it.

From open data to open information

In some contexts tender notices are published in paper — for example on a noticeboard, in a government building — with no way of knowing when new tenders are published. Technically this tender is open for anyone to bid for, but in practice it’s anything but. The same principle applies to data.

Open data needs to be useful and usable, otherwise it might as well be kept on a USB stick in a desk drawer. What’s the point of having a spreadsheet full of great data if you’ve no idea what any of it means?

Standards mean that when someone’s gotten hold of your data, it’s useful — they know what they can do with it, or at least learn from others who’ve used the same kind of data before.

For the information contained in that data to be genuinely open, it needs to be put to use. It needs eyes on it, to be explored and analysed and re-presented and reported on. Standards help with that by providing a quicker path to giving meaning to data than is possible with data alone.

If your data relates to something that’s liable to corruption or manipulation, then standards become even more important: they mean your data is more resilient to attempts to bias it by way of not publishing key information, and it’s more likely to be trusted.

Being open means not going it alone

Most open data standards have a community around them, who provide help, advice and resources. Often, they’ve done a lot of the hard work of modelling concepts in data, and good standards are well-researched and recognised as being trusted. From government contracts to water quality to medical data, communities of people doing the same thing in different places are developing standards, making all of their data more valuable.

Those communities write tools — quality enhancing, data checking, analysing and processing tools that make the data easier for anyone to use, right away. They’ll provide templates, guidance and support. And, they’ll help you put your own data to use — helping you understand how what you are modelling might have new applications.

We’ve worked with a wide range of organisations and sectors, helping them open their data and reap the benefits. We never cease to be amazed by the additional benefits that open data standards bring — the communities that are built, the understanding of one’s own data that comes from working with a standard, and the possibilities that all of this unlocks.